Roberto Téllez-Vizcaíno has a master’s degree in applied geosciences and is passionate about volcanoes. He will soon be a doctoral student at the Potosino Institute of Scientific and Technological Research. Born curious, his interest in volcanology dates back to his hometown Colima, the place of the Colima Volcano of Fire. He conducted research for his master’s thesis on the stratigraphy and volcanology of the Xoxoctic Tuff of the Los Humeros Volcanic Complex in Puebla, Mexico. He is the creator of the Facebook page on volcanic disclosure “Infovolcán“, with more than 20 thousand followers.

In early March 2022, I had the opportunity to join a scientific expedition on a visit to the Revillagigedo Islands. This volcanic archipelago is located in the Pacific Ocean to the west of México, around four hundred kilometers south of Los Cabos in the Baja California Peninsula. Once there we were so lucky to visit the uninhabited San Benedicto Island, the northernmost of the four islands that comprises the group. It is by far the best fieldwork trip I have ever done; a magical place and a once-in-a-lifetime experience that I will never forget.

These volcanic islands were formed on the northern end of the Mathematicians Ridge, an mid-ocean ridge that was abandoned ca. 3.5 million years ago when ocean spreading shifted to the East Pacific Rise ~400 km to the east. San Benedicto Island is just the summit of a huge and active submarine volcano formed on the seafloor of the Pacific Ocean at a depth of around 3 km. The Revillagigedo Islands are interesting because they are composed of a wide variety of magmas and volcanic rocks, unlike the majority of volcanic islands in the Pacific that are predominantly ocean island basalts (OIBs). Volcanological investigations about San Benedicto are scarce, but the few there are mention that this island is mainly trachybasalt and trachyandesites, rock types that are typically not expected from mid-ocean ridges.

San Benedicto became famous among geologists at the middle of the last century due to the eruption of Barcena volcano in 1952. Adrian F. Richards was lucky enough to visit the island just before the eruption began and continued his visits during and after the volcanic period ended. Barcena’s tuff cone definitely is the most prominent feature of the entire island, from the distance it is difficult to realize how big and tall it is. There are other features that comprise the landscape: the remains of an older cone called ‘Monte Cinerítico’, beautiful beaches around the island like ‘Caletilla Banda’ and the amazing cliffs from ‘Cráter Herrera’ at the north, that can be seen from the boat and satellite images. Evidencing the recurrent explosive magma-water interaction through time on the volcanic island construction.

The scientific field trip leader, Douwe van Hinsbergen, a geologist and tectonicist from Utrecht University, gathered an amazing team of geologists, geochemists and geophysicists in which I was blessed for being invited. The team was constituted a team of specialists who together turned the volcanoes inside-out: a) Douwe, Romy Meyer, PhD student in paleomagnetism at Utrecht University, Mélody Philippon, a tectonicist from the University of the Antilles at Guadeloupe, and Pete Lippert, a paleomagnetist from the University of Utah at Salt Lake City, USA; b) Janne Koornneef, an isotope geochemist from the VU University of Amsterdam and Laurens Tromp, her MSc student; 2) geochronologist Yamirka Rojas-Agramonte and coastal geologist Christian Winter, from University of Kiel, Germany; 3) Pablo Davila-Harris, volcanologist from IPICYT at San Luis Potosí, Mexico, and myself. All of them, incredible human beings.

The main purpose of the project is to test the hypothesis that the anomalously explosive volcanism of San Benedicto may be caused by past subduction that occurred at the location of the Revillagigedo Archipelago in the Mesozoic, as witnessed by a deep slab that is located in the lower mantle below the islands (http://www.atlas-of-the-underworld.org/Socorro/). Recent findings elsewhere have suggested that retired mantle wedges may remain more or less in place for 150 million years or more, and if that is the case, we could still find the traces of old subduction in the Revillagigedo volcanoes, with major repercussions for mantle convection processes. To test this, part of our group took samples to study zircon minerals from the islands to see if zircons much older than the volcanoes remain. Another collected samples searching for olivine to analyze its melt inclusions and origin to decipher the mantle composition below the volcanoes. The paleomagnetists did not really study the volcano itself, but took samples to study the intensity of the Earth’s magnetic field. And finally, Pablo and I collected samples to analyze the petrology, overall volcanology and explosiveness of the eruptions for volcanic hazard assessment. Our main goal was to take all the data we can to reconstruct the eruptive history of the island.

The trip began at San Jose del Cabo in Baja California Sur, where we all met and defined the fieldwork plan each group had to do. We started our journey to the Archipelago in the ship called ‘Quino El Guardian’ which had a fantastic crew. We set sail at night and started familiarizing with everybody the first day. Getting used to the movement of the boat was somewhat complicated on the second day, which was a travel day. But when waking up in the morning on the third day, the suffering of the previous day was immediately forgotten upon seeing the majestic sunrise over San Benedicto Island.

After that unbelievable image, we had breakfast and got ready for the action. I had never before this field trip done any wet landing (at the end of the field trip we were all experts), but for getting into San Benedicto it was the only option. A dinghy took us the closest we could get to Caletilla Banda beach and from there we jumped with all our stuff right to the water, among manta rays and blacktip sharks, an awesome experience at an awesome place. While drying and changing our clothes, we contemplated the huge walls of the Barcena tuff cone in front of us and realized we were finally there.

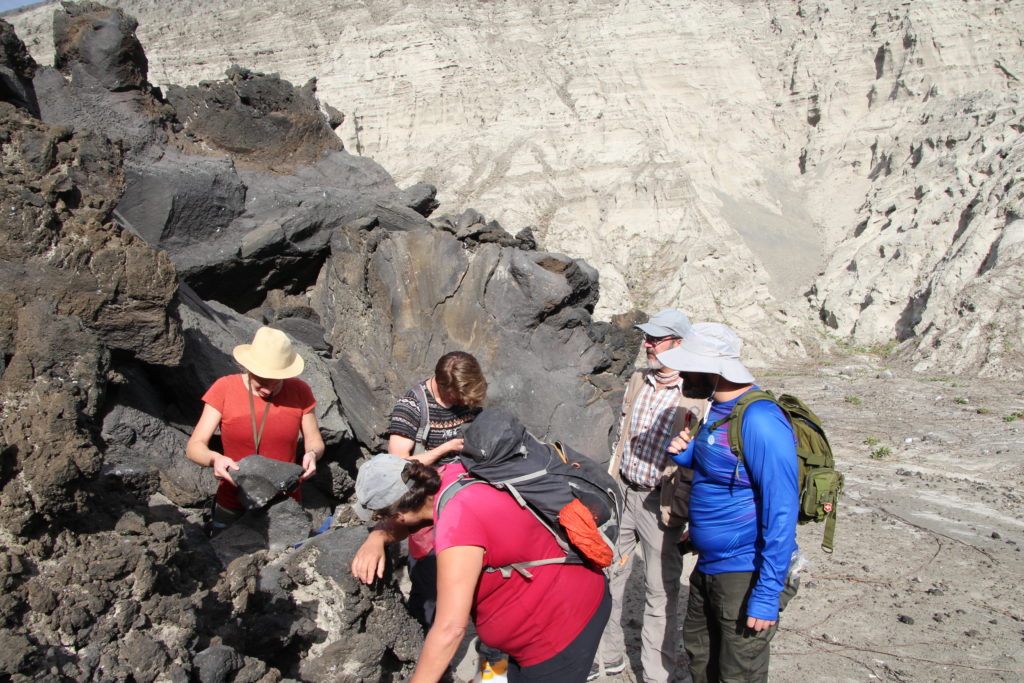

First, we went south to look at the lava delta that burst out one side of the Barcena cone. We managed to take some samples of the lava while keeping an eye on the albatrosses next to us. The paleomagnetic and the olivine team stayed longer there while Pablo and I went closer to the outcrops of the Barcena cone. We divided the work in order to get stratigraphic information, samples from different levels, photos, GPS points, and all possible notes, the data we need to study the history of the eruption.

Then we reunited with Janne, Laurens, and Pete and together went climbing up trying to find a path to the summit of Cráter Herrera. The hike up was an entire adventure itself, going through the gullies of ash was challenging. There were parts where the moment we stepped on the ground it crumbled, sinking us in ash up to above our knees. We kept sampling ash, blocks and lithics as well as taking stratigraphic data while going upward. Sadly, we couldn’t make it till the summit – the last two meters turned out to be impossible to get up – so we went back to the beach, got all our stuff back in the dinghies and went with them to the sides of the Herrera Crater.

After a ride, we found a rocky beach. We thought we could swim until there, sample and swim back to the boat with the sample’s box. The dinghy rider got us the closest he could to the cliff where Janne, Laurens and I made a very risky wet landing and swam till the rocky shore. There we got samples from lava and ignimbrite outcrops, samples that somehow, we succeeded in taking out after we were rolled over by the waves several times. Then we went to the Quino and organized the samples. The next day we woke up on Socorro Island but that’s another story.

Bárcena is the most striking feature of San Benedicto Island, and in its outcrops, it has a lot of geologically interesting information we could see in the field. The cone presents typical tuff cone structures for example, the relatively small parallel stratigraphy combined with cross-stratified layers of tephra ranging from fine ash to some big bombs and boulders. It also shows magma-water interaction evidence like bomb sags, slumps and plenty of ash aggregates like accretionary lapilli and pellets. Most of this young cone is formed by fine material, but there are also large pumice blocks, some of them show a little banding and hopefully, interesting mineral phases. Between the tephra layers, there are also some coarse grained breccias rich in lithics, perhaps from erosion or eruption of the inner conduit and crater walls, entrained within the columns or pyroclastic flow deposits. Definitely walking through it and taking samples was a rough and dirty work.This has been the best field trip ever, and San Benedicto Island is a place that will stay in my mind forever. I had the awesome opportunity of joining this trip that gave me fantastic friends, amazing memories and invaluable experience. I want to thank Pablo and Douwe for trusting me and inviting me to the project. I also want to thank the funding agency for this project NWO, and the institutions that make this field trip possible giving us all the permissions needed and also a lot of field work help, IPICYT, SEGOB, SEMAR and CONANP. What’s next? Probably the best is yet to come, a lot of lab work, data processing and interpretations. And if the results are the expected ones, we might go back to the archipelago sooner than later. Can’t wait!

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.