Scott Hassler works for the common good at The Wilderness Society, focusing renewable energy, climate adaptation, and wild land protection and restoration, primarily in the Western United States. He continues to research the environmental effects of extremely large meteorite impacts and teaches a bit at UC Berkeley. Possibly too many of his travels, geologic and otherwise, are detailed here.

I’ve gradually been exploring the Colorado Plateau on my summer holidays, generally via long road trips, camping my way throughout the region looking at rocks, hiking, and taking photographs. There are plenty of federal and state lands to visit – national parks, national monuments, state parks, national forests and national conservation areas, to name a few. Generally, I’ve worked my way west from California, which means crossing the Mojave Province: enough Basin and Range geology for a lifetime. The Mojave has its beauty, but it has never been very attractive to me. There are exceptions; the Alamo Breccia boggles my mind every time I think about it.

The Utah and Arizona portions of the Colorado Plateau expose Precambrian to Paleozoic (Grand Canyon) and lower Mesozoic rocks (Zion, Canyonlands, Arches, Capitol Reef, Escalante-Grand Staircase). This is the archetypical red rock country of the American Southwest. The regional also includes some younger and equally wonderful exceptions (Bryce, Cedar Breaks), exposed on some of the higher subplateaus. There isn’t a lot of younger Mesozoic rock; I presume this reflects erosion as the convergent plate boundary to the west became more robust, both changing the regional gradients and subjecting the area to long periods of subaerial erosion as well as later Basin and Range extensional events.

There are plenty of Cretaceous rocks on the Colorado Plateau, mostly to the east in Colorado and New Mexico. I finally reached this area a few years ago. It’s a nice drive from Albuquerque northwest onto the Plateau, crossing the Rio Grande Rift and working around the Valles Caldera complex. I quickly discovered that in contrast to further west, there was a much greater breadth of archeology to explore.

There are archeological sites all over the Plateau, which indicate episodic human occupation for several thousand years. The location, lifestyle, and populations have changed, seemingly reflecting climate variations, cultural innovations and migration patterns. Most of the Utah and Arizona sites, which occur throughout the stratigraphy, seem relatively small. This could reflect any number of ecological, climatological, and cultural variables, but I get a distinct sense of fewer people, or at minimum people living lighter upon the land.

My most recent trip was a south to north transect which took in several of the major archeological sites on the southwest Plateau: Chaco Canyon, Ute Mountain/Mesa Verde and Chimney Rock. Chaco Canyon National Historical Park fully earns its designation as a World Heritage Site. The park includes the ruins of at least 11 great houses – large freestanding structures that may have housed 1000s of people between the 9th and 12th centuries. There are also numerous smaller structures, ranging from what appear to be family homes to large kivas. Chaco’s history is controversial. There’s a historical unconformity, as it were, between the time when the area was finally abandoned and the origins of modern Native American groups. There are traditional stories and some archeology connecting the ancient Puebloans – the people who built Chaco[1] – to modern groups including the Hopi and Zuni, but the scientific threads are frayed.

In any event, the great houses reflect several centuries of intermittent occupation and construction, but it’s uncertain if the area was a major population center. Chaco’s occupation and culture are directly tied to climate evolution across the west. Drought equals contraction, wet means expansion. However much it was used, Chaco was a cultural center. The Chacoan road network essentially radiates from the canyon to points at least 60 kilometers distant. There’s interpretation that the great houses served important ceremonial/religious functions. The area also has very cool archeoastronomy sites, which show a sophisticated understanding of solar and lunar rhythms. I was also intrigued to learn that some of the major sites within Chaco and others up to 100 kilometers to the north in Colorado align in an almost true north geographic line. What this means is speculative.

Chaco Canyon is 25 kilometers long, north-northeast to south-southeast west trending, and up to 2 kilometers wide. It’s cut by the incised Chaco Wash, which meanders between flat-lying cliffs of Upper Cretaceous Menefee Formation overlain by Cliff House Sandstone[2], with an alluvial cap. Both formations comprise varying amounts of interbedded sandstone and shale; they represent shoreline facies of the Cretaceous Interior Seaway. The combination gives the drainage steep walls (a thick sandy unit of the basal Cliff House) and a flat floor (Menefee). My geologic guidebook interpreted this as a barrier beach complex; the mesas of Chaco Canyon’s southern margin represent the barrier beach, the canyon per se was the back beach lagoon, and the northern margin was land. I couldn’t really evaluate this in my explorations. There’s been too much lateral erosion and downcutting since the Plateau was uplifted. The strata looked fairly continuous across the canyon; there was no evidence of any significant faulting.

You will have realized by now that Chaco Canyon and its culture are interesting. To explore the area, I drove to most of the great houses (it’s an American national park, after all) and hiked out of or along the canyon to the others. Only a few structures have been excavated and restored; most are ruins, basically curvilinear, room-shaped mounds of rock.

Nonetheless, I noticed two consistent patterns of geologic interest.[3] First, the style of masonry in the great houses changed through time. This has long been recognized by archeologists, who distinguish four types of construction. Basically, the older, bigger great houses are built from plates of thin (cm-scale) beds that are somewhat randomly laid together. This style is followed by two variations of alternating layers of finer and thicker beds, clearly worked to match, creating a more aesthetic structure. Finally, the younger buildings were made from bigger blocks of thicker sandstone, which looked cruder to my eye. Erosion and reconstruction might have biased me somewhat, but these trends seemed clear.

One of the finely worked styles of Chaco masonry, Hungo Pavi Great House, Chaco Canyon National Historical Park

Second, from observation on my hikes, the source material for the great houses was local Cliff House Sandstone. This makes sense, why carry rocks for long distances? The ancient Puebloans did gather far-sourced materials when necessary; the wood used in all the structures is estimated to have been sourced at forests up to hundreds of kilometers distant. In addition, they were great engineers; there are many examples of both carved stairways and ramps that ascend the basal cliff to the thinner units above, connecting to the Chaco road system. The ramps are impressive; they imply piling up thousands of cubic meters of alluvium, and in at least one case, building and installing a wooden ladder/platform complex into a sheer cliff.

I noticed a distinct trend in Cliff House Sandstone as I wandered around (who follows trails?). Once I got above the basal cliff-forming unit, the abundance of exposed bedding changed, qualitatively at least. Above the rim of the Canyon, hiking was fairly easy as there was little thin-bedded sandstone, just abundant siltstone and shale, which made for fairly easy contour walking. In contrast, away from the main Canyon, the density of thin sandstone beds increased, and more scrambling was necessary.

My untutored speculation based on these two observations is that the ancient Puebloans preferred to work with the most easily quarried close by materials. They preferentially removed the thin sandstone beds first, which may explain the lack of these layers along the canyon closest to construction sites. It would have been relatively easy to excavate thin beds by clearing away the softer surrounding fine-grained material, especially if a wetter climactic period[4]. The sandstone blocks of the later great houses would have required actual quarrying to remove and shape. While this trend in architecture could have been for cultural reasons, maybe it was also out of necessity. All the nearby good stuff was used already.

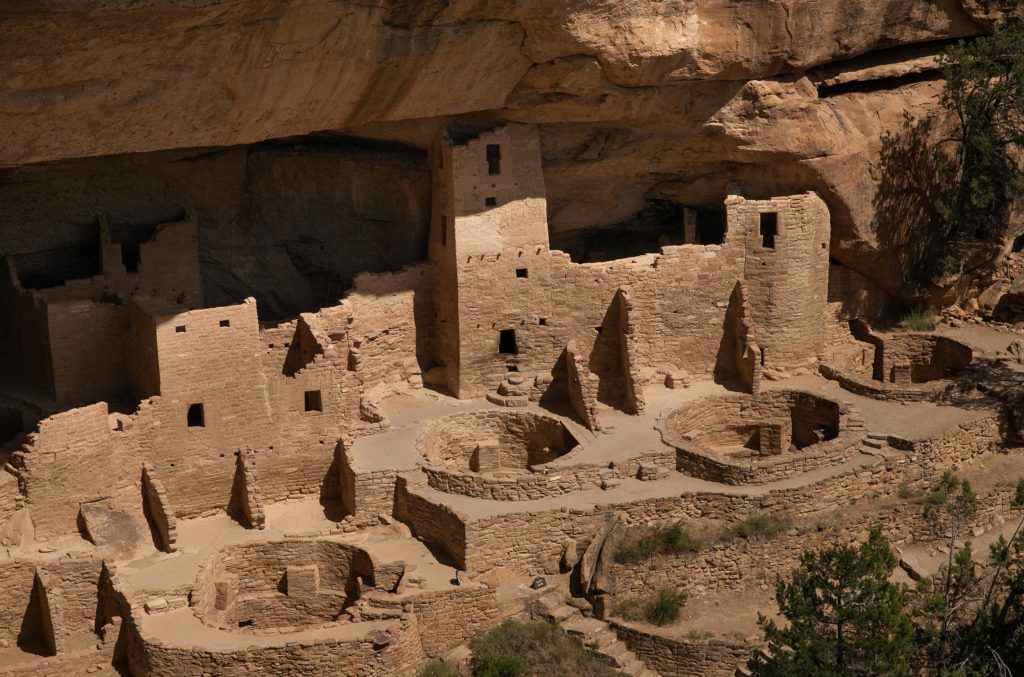

After leaving Chaco Canyon, I visited both Mesa Verde National Park and the Ute Mountain Ute Tribal Park[5], which is just south of Mesa Verde and contiguous with it. Here in Southwestern Colorado, the structures were also built by the ancient Puebloans, but are younger than Chaco Canyon’s great houses. This is interpreted as a climate-driven migration to higher, wetter areas. There are also suggestions that the Puebloans retreated to more defensible sites in the cliffs, perhaps in response to periods of cultural collapse, which of course could have been climate-driven.

In both Parks, the stratigraphy includes much thicker cliff-forming sandstones separated by thinner shaley units. The ancient Puebloans took advantage of this, the geology of the Cretaceous Interior Seaway. When building their amazing great houses into recessive ledges within the cliffs, they chose areas that were south-facing for warmth, big enough for building multi-story, tiered structures, and easily accessible to mesa tops, presumably for agriculture[6]. However, they don’t seem to have quarried the local cliff material for their buildings, but to have brought in thinner bedded material, presumably from higher and lower in the stratigraphy.

There are certainly exceptions to the rule of using local material. Aztec Ruins National Monument (not Aztec, but they looked that way to the Spanish in the 17th century) in northernmost New Mexico is between Chaco Canyon and the Mesa Verde complex, both in space and time. Its architecture looks more like earlier Chaco to me. At Aztec, an excavated and restored wall contains multiple layers of a metamorphic greenstone amid the usual thin-bedded sandstone. It’s pretty. This material would have most likely come from many tens of kilometers away, likely to the north in the San Juan Mountains.

My final stop on this archeological transect was in Southern Colorado, at Chimney Rock National Monument. This site is higher in the Cretaceous stratigraphy; Lewis Shale overlain by Pictured Cliffs Sandstone, representing the next transgressive/regressive sequence after the Menefee/Cliff House sequence.

At Chimney Rock, the ruins of a single great house occupy the top of a Pictured Cliffs-capped butte. It’s a high point, in fact the US Forest Service maintained a fire lookout station here (on top of the ruins!) for many years. The great house is small on the scale of Chaco Canyon, and was built by people who were either part of or were influenced by Chaco culture, based on its design and other archeology.

Chimney Rock National Monument. Great house ruins are on the rounded butte to left. Companion Rock and Chimney Rock at center and right.

Visitors must take a guided tour of the site (it’s both remote and fragile), so I was unable to test my idea about the builders using local materials. The mesa top was also very hot and exposed. I was on the last tour of the day and it was easily 95 F. In any event, the builders again performed an impressive engineering achievement; they both fit the great house into the small footprint of the mesa top and hauled all the building stone uphill from wherever it was quarried.

So, why build a great house on top of a mesa? Chimney Rock and its partner, Companion Rock, both stacks of Pictured Cliff Sandstone, are just to the north of the great house on the mesa top. Viewed from the ruins, they form a prominent notch in the horizon. Here’s the cool part; the full moon rises in the notch at sunset near the day of the Winter Solstice, but only every 18.6 years during the Major Lunar Standstill[7]. Someone – the ancient Puebloans or their antecedents – figured this out. The great house is thus thought to be a ceremonial site which was no doubt a scene of great activity every couple decades. Chimney Rock is still in use by local Native American groups, so don’t plan on coming here for the next Major Lunar Standstill until 2021.

I had read about archeoastronomy before coming to Chimney Rock, but seeing the evidence was very dramatic. It took many years, if not generations, of observation from just the right place to discover Chimney Rock’s unique location. It took untold work to build the great house, and to learn to build great houses using the best materials from across the Cretaceous Interior Seaway. These long-time frames speak to the endurance of the ancient Puebloan culture the depth of its engineering and astronomical knowledge and to overall human fascination with what happens in the sky at night.

[1] “Ancient Puebloans” seems to be the most accepted current term for these people. They used to be called the Anasazi.

[2] The Cliff House Sandstone is named for the archetypical Cliff House dwelling in Mesa Verde National Park, which is about 160 kilometers north-northwest of Chaco Canyon.

[3] These are of course my observations, I don’t know if they are original, or even accurate. Any archeologists reading this, please forgive me.

[4] I have certainly done this many times while studying cm-scale meteorite impact deposits within basinal sequences.

[5] UMUTP was stunning. I took the required day-long guided tour, which was an opportunity to explore several well preserved but unexcavated ruins. Much more interesting than the huge tours at Mesa Verde. Highly recommended; make reservations in advance.

[6] There is speculation that these sites were also more defensible; there is clear evidence of horrific cultural collapse at the end of the Chaco culture.

[7] Here’s what I learned about a Major Lunar Standstill. The moon’s orbit around the Earth oscillates, gradually causing the moon to rise at different points on the horizon. A single oscillation, i.e., N to S to N, takes 18.6 years. The moon seems to pause for about three years at the end of each cycle, rising at more or less the same point on the horizon before beginning to move back in the opposite direction. This pause is the Standstill.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.