Catherine Wheller is at the pointy end of her PhD at The University of Melbourne, Australia (excepted completion early 2017). Her research involves using phase equilibria modelling of mineral assemblages to investigate the formation conditions of high-grade metamorphic rocks. She produced a new thermodynamic model for sapphirine and is applying this model to rocks collected in southern Madagascar. Throughout her postgraduate studies she has been involved in teaching practical and field classes and is starting a position as a casual lecturer of metamorphic geology for a second year course in 2016. Catherine writes extensive field stories on her website and can be found on Twitter as @catinthefield. She can be found with her trusty Olympus camera taking photos of the stars and longing for better skies than suburban Melbourne. Catherine was also a finalist in the three-minute thesis competition. You can watch this at the bottom of this post.

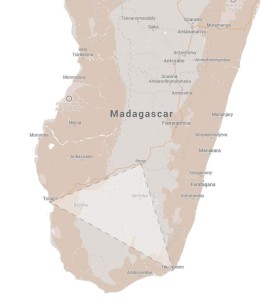

Figure 1: Area of interest in southern Madagascar – triangle between Ihosy, Fort Dauphin and Tuléar. Source: Google Maps

I get quite excited when people ask about my PhD. I shrug off the questions about ‘when will you finish’, ‘what will you do next’ and steer the conversation to ‘let me tell you what I did’ which is infinitely more exhilarating. After computer modelling for two years – working out new models for how minerals behave under changing pressures and temperatures – I am eager to apply this knowledge to actual rocks. I travel to southern Madagascar to study rocks formed deep in the crust, during the collision involved in the final formation of the super continent Gondwana. We are collecting samples of metapelites in order to find out under what conditions they formed. This involves understanding the mineral assemblages and insights into the scale of equilibrium and reaction textures – at such high temperatures that have been estimated here (between 850 and 1000 degrees Celsius) we expect to find complex relationships between retrograde and prograde textures preserved.

An interesting feature of this terrane that peaked our interest in the first place is that it is oxidised – that is, lots of coexisting magnetite – and this has repercussions on the way that minerals behave. Adding ferric iron (Fe3+) into the chemical system means that minerals that have the space to accommodate a ferric proportion may be stabilised to lower temperatures. An assemblage that has previously been thought to be diagnostic of ultra-high temperature (UHT; >900 ºC) terranes may be stable to lower temperatures, thus potentially changing the tectonic implications of this terrane. In this case, the mineral assemblage sapphirine + quartz. This assemblage has been recorded in southern Madagascar, and with recent additions to the thermodynamic model of sapphirine, we are now able to model sapphirine in oxidised terranes. We anticipate the peak metamorphic conditions of this terrane to therefore be lower than previously estimated.

For more information on this development, please see this publication.

While the geological story is fascinating, I am going to stop here and give you some insights on fieldwork in remote southern Madagascar. A coup in 2009 seems to have scared off the tourists who usually visit the coast, and it is rare that we see another foreign group. Regardless, the villages that we are heading too have not had outside visitors for a decade. We are travelling by Toyota Hilux, – myself, Steve Boger, Richard White, and our friend and guide, Auguste Razafinjoelina. At the time our story starts, Steve, Auguste and I have driven down the east coast over four days, from the capital Antananarivo through Mananjary, Farafagana to Fort Dauphin (Tôlanaro). We have been sleeping under the moonless sky and in zebu fields and enjoying the laid-back ferry punts. We pick up Dick in Fort Dauphin and head out west to the desert.

Figure 4: One of the nine ferry crossings. Sometimes we had to siphon our diesel into a motor. Photo: Catherine Wheller

Cactus country! This area of Madagascar is drier, and is known as the Spiny Forest of the south.

“Of all of Madagascar’s southern habitat’s”,

David Attenborough narrates,

“none seems more challenging than this … the forest that grows here, is one of the strangest on Earth”.

Houses are wooden, but have a distinct tilt to them and Prickly Pear cacti used for security surround the villages. But the cacti have run wild, and if you stick your head out the window you get a mouth full of spikes. Everything is spiked. “The plants are viciously spiny” says Attenborough, not that we need to be told. Not much outcrop here though luckily, or if it is, the effort/thrill ratio is so huge that it would not be worth the pain.

We see our first baby baobab (‘all baobabs are boabs, but not all boabs are baobabs’) and they are steadily getting bigger the further inland we travel. Octopus trees carve through the forest and collect what little water there is on their spikes. Euphorbias protrude like sausages from the ground and the land looks extremely hostile. But strangely enough, it is also our first opportunity to potentially spot lemurs as they would not be so hidden. These are tough lemurs though, “they can go without drinking at all” and survive by picking small leaves of the Octopus Tree between the spines. They also take the fruit of the Euphorbia, not minding that the tree also secretes a chemical that can burn through skin. Geez, who picked this field area.

The tracks are better than on the east coast, as they are drier and it is also less humid. Temperatures during the day though are in the high twenties. We stock up on more rice, eggs, tomatoes, and mofo-gasy (muf-gas) and mofo-baolina (muf-bol) – pancake like food that are like English muffins and deep-fried doughnut balls respectively – from small stalls on the side of the road. For lunch we stop under a shady baobab and get out the map, instantly attracting a crowd in what we thought was a deserted place.

The map shows a large village called ‘Tranamaro’ and we decide we will head there for the night. The choices are usually to find a flat spot away from the road and not too close to villages to camp, ask at the local village for a ‘hotel’ (a room in a hut), or to camp in the village depending on the security status. We arrive in Tranamaro to find that it is not considerably big; in fact it seems the most under-developed that we have travelled through. Much less welcoming as well, although the children are always happy to see us. An older woman put us up in her ‘hotel’ – two rooms and a small kitchen. We use sleeping bags or sleep on the floor to mitigate against fleas. She cooks us dinner (chicken with rice) and recounts her story on the security situation in the Anhosy region complete with graphic arm movements showing slitting throats and chopping off of hands. In rapid Malagasy and unsmiling she describes how the bandits come into the villages in the early evening and threaten them – hopefully that is all that they do. The looks on the faces of my colleagues tell me this is a serious situation and this is possibly a turning point in our field season. Her descriptions are terrifying and that night Auguste decides that I am to sleep in the back room with the other three out front and a visiting gendarmerie with an AK-47 at the door. Auguste demonstrates what he would do with his machete if they climb through the window. However the machete stayed under the bed and, but for not much sleep, the night was uneventful. We are happy to leave Tranamaro (though what an experience).

The army (‘gendarmerie’) are coming down from the capital in droves to combat recent bandit activity- a 500 strong force for the 200 bandits. The consequence of this is unknown – either they will flee to the hills, or they will fight. We decide that the main risk would be either being caught in the middle, or be mistaken for army personal. Past expeditions in the area have taught us that as foreigners we should not be targets, so we decide to continue inland to the relatively large village of Tsivory.

A few hours up the road from Tranamaro is Maromby – a much bigger village with stable, brick buildings and a proper administration. The people seem much less worried and I can hear western music coming from a radio. We should have stayed here! The local chief is an administrator, and we find him with a typewriter in a government building. His computer was stolen by the bandits, but the typewriter does the job. Today we are looking for metapelitic outcrop, evident as a magnetic high on our map, and we ask around to find a track to the area. A few false leads and we find a local sapphire mine who have dug tunnels right under the road (no cars have been here for a decade). An elder from what I call the ‘goat village’ helps us find a track. I make friends with ‘Nini’ from the goat village and she shows me her house – mud walls and thatched roof with rice cooking on a fire in the corner. We realise that the 2006 mapping project would have come through here – they remember an older German man who came through eight years ago – the last vazah (foreigner) who had been in the village. We finally get to our outcrop – in the midst of cactus central and fire. It’s a good one though, and we’ve been searching for hours. Into the cactus we go.

We decide to try and continue on to Tsivory by taking a shortcut west, but we meet a man walking with a stick (polio?) who takes us to the edge of a track all the while refusing to let us drive him. We get to a creek bed but are told that we should not keep going because the bandit village is just up the road.

We backtrack and decide to go the long way to Tsivory and end up staying the night at Maromby. We are put up in a school room on the floor. We attract a crowd around dusk and Auguste plays Malagasy music from the car which turns into a mini-dance party for the kids. When it gets dark everyone scampers except for some teenagers who watch us cook. We shoo them off, stick candles to the bottoms of cans and create a dining table out of the teacher’s desk.

We wake up to find two of our jerry cans full of diesel are gone. The car was locked, but the back trailer is not so secure and we were too involved in dinner to be vigilant. We tell the chief, who is embarrassed, but there is nothing we can do, and we leave the village minus 40L of fuel and much less naive that when we started.

Figure 9: The three stooges – Dick, Steve and Auguste. We hadn’t realised our fuel was gone at this point… Photo: Catherine Wheller

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.