Rehemat Bhatia is a geochemistry/micropalaeontology PhD student at UCL and my supervisors are Prof. Bridget Wade, Dr David Thornalley, Prof. Melanie Leng (BGS), Dr Bradley Opdyke (ANU) and Prof. John McArthur. You can follow her on twitter @rehemat_.

My experience on board the IODP ‘Virtual Drillship’ at the MARUM – Center for Marine Environmental Sciences and the IODP Bremen Core Repository (BCR), University of Bremen, Germany

Samples and data collected during scientific cruises can greatly help to broaden our understanding of the Earth. The International Ocean Discovery Program is a research collaboration which aims to recover data from ocean sediments and rocks. It is made up of 26 member countries and is mainly funded by the NSF (U.S.), ECORD (Europe) and MEXT (Japan) (there are additional partners as well). IODP has 3 drilling platforms – The JOIDES Resolution (riserless drilling), the Chikyu (riser drilling) and a mission specific platform (designed to fulfil specific drilling objectives and work in areas where the JOIDES resolution and Chikyu can’t work e.g. areas covered in ice and shallow waters). IODP has changed its’ name several times, starting off as DSDP (Deep Sea Drilling Project), then ODP (Ocean Drilling Project) and then IODP (although the name changed from Integrated Ocean Drilling Project to International Ocean Discovery Program in 2013).1

For 1 week during March 2015 a mixture of 30 graduate students and post docs from all sorts of scientific backgrounds became the crew of an IODP drillship at the MARUM and IODP Bremen Core Repository at the University of Bremen in Germany. This was the first ECORD training course, which aimed to help train (geo)scientists from both academia and industry from around the world to participate in offshore drillship expeditions. The course was led by scientists from various countries across Europe, all of whom were super enthusiastic about their subject area.

Cruise activities

On board a scientific cruise there are usually about 30 scientists (mission specific platforms have smaller scientific parties). The disciplines in which they specialise in depends on the focus of the cruise. An expedition’s main scientific objective has to fit in with at least one theme of the IODP Science Plan (climate and ocean change, deep life, deep processes and their effect on the surface environment and geological hazards).2

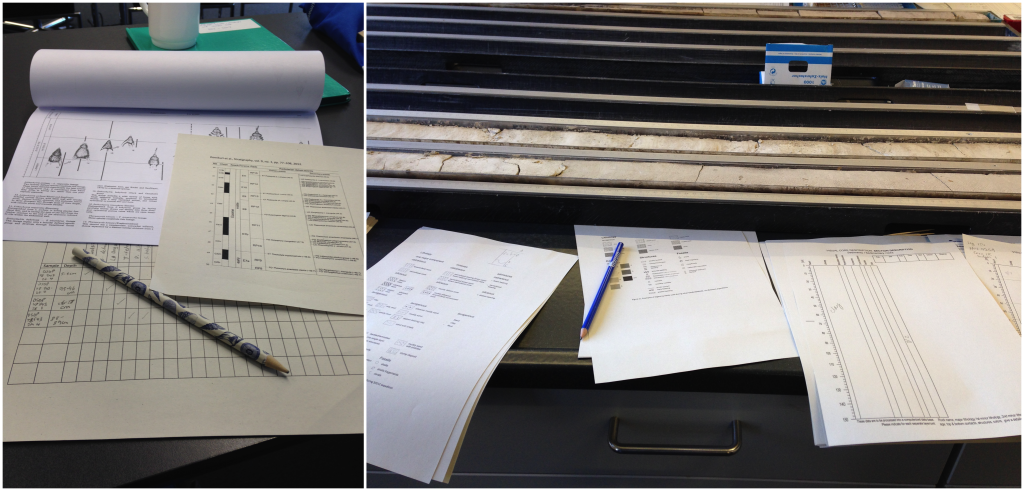

For most of the practical sessions we were divided up into three groups, with a range of expertise and experience between us, including micropaleontology, microbiology, seismology and petrology. The shipboard activities we were able to try were biostratigraphy, physical property/core logging, sediment core descriptions, hard rock descriptions, pore water acquisition and analysis, high resolution linescan imaging and colour scanning.

When a core comes on deck, it is split into two so there is an archive half and a working half. The working half can have samples taken from it whilst an archive half is left intact for core descriptions, non destructive analyses and high resolution imaging. The top of a core always has a blue cap and the bottom has a transparent cap.

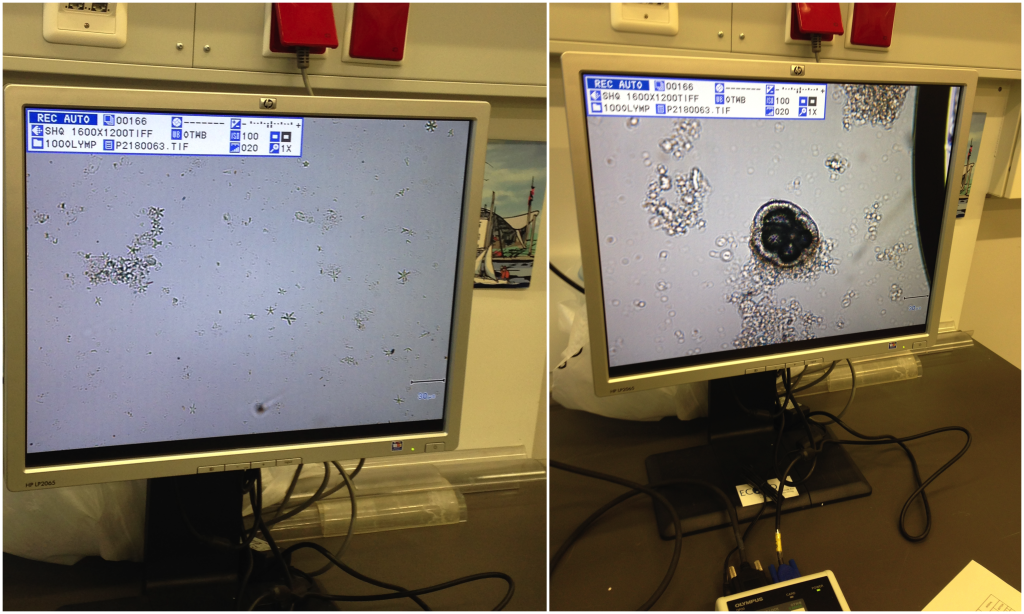

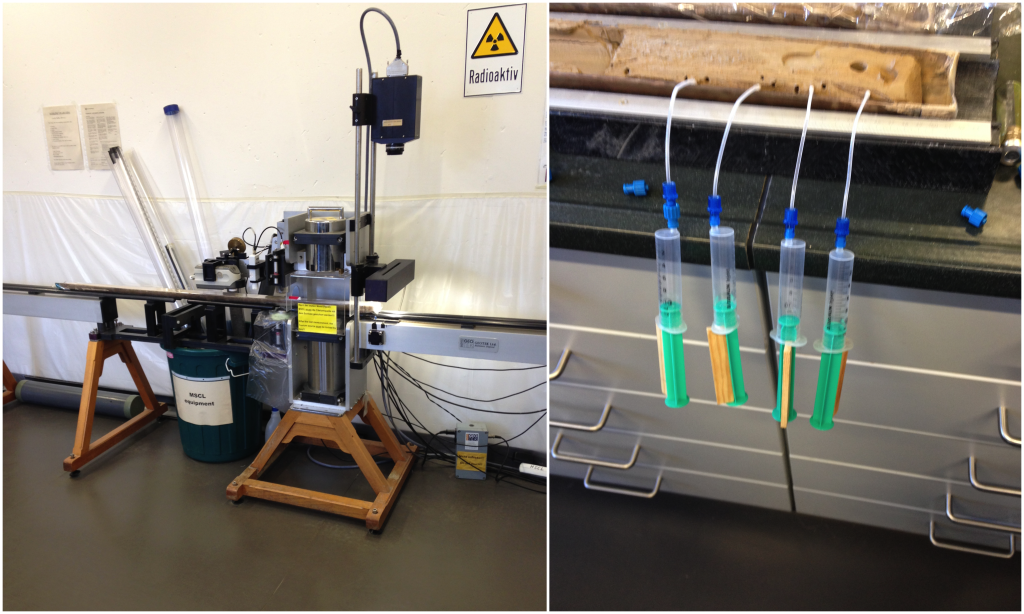

[A] Biostratigraphers help to date the core material – they can use the microfossils (like foraminifera, radiolaria, diatoms and nannofossils) in the sediments to know what time period the core is from. The biostratigraphic data in conjunction with the paleomagnetic data helps to accurately constrain the age. [B] Physical property specialists record core data such as resistivity and magnetic susceptibility. Core logging methods are semi automated, high resolution and fast and thus have an advantage over analytical methods. A multi sensor core logger (MSCL) is used to get colorimetric, natural gamma radiation and magnetic susceptibility data, whilst moisture and density data is collected by measuring the dry and wet weight and volume.

[C] Discoaster nanofossil species on a smear slide (left); [C] Foraminifera specimen from a sediment smear slide

We were also introduced to stratigraphic correlation and creating a composite core record. This involves correlating different cores which are taken in the same location but which have different amounts of recovery. So if one core has a section missing which another core recovers then the two can be put together to create one whole composite record. From these composite core records, changing rates of sedimentation can be identified.

IODP proposal writing was also covered – we split up into groups and had to come up with a drilling site and a mini proposal. This was definitely a challenge given that not everyone in the group was from the same background and we had to find a drillsite that would satisfy all of our research interests whilst keeping in line with the IODP Science Plan!

[F] We were also shown the Bremen Core Repository. This contains 154 km of IODP, ODP and DSDP cores from the Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea, Black Sea and the Arctic Ocean (> 230,000 tubes!). Cores are stored at 4°C, wrapped in film and organized in racks. Overall, I had a fantastic time – all the participants were super enthusiastic and there was a good work hard play hard ethic too. One of the best parts about the course was that not only did you get to see how your own background was relevant on board a cruise, but how it fitted into other areas of expertise. Understanding how different disciplines relate is crucial so that every team of scientists works effectively together. I’m so happy I went on the course and I’d thoroughly recommend it to other PhD students and early career researchers!1 International Ocean Discovery Program [Online] Available from http://www.iodp.org/ (accessed April 2015)

² IODP Science Plan 2013 – 2023 [Online] Available from http://www.iodp.org/science-plan-for-2013-2023 (accessed April 2015)

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

![[D] Example of a hard rock core (left); [D] Lots of hard rock cores! (right)](http://www.travelinggeologist.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/4-1024x614.png)