Jeremy recently completed his M.Sc (Geology) at the University of Melbourne, Australia. He enjoys using geochemistry to provide insight into large scale tectonic processes and is planning to commence a PhD in 2017.

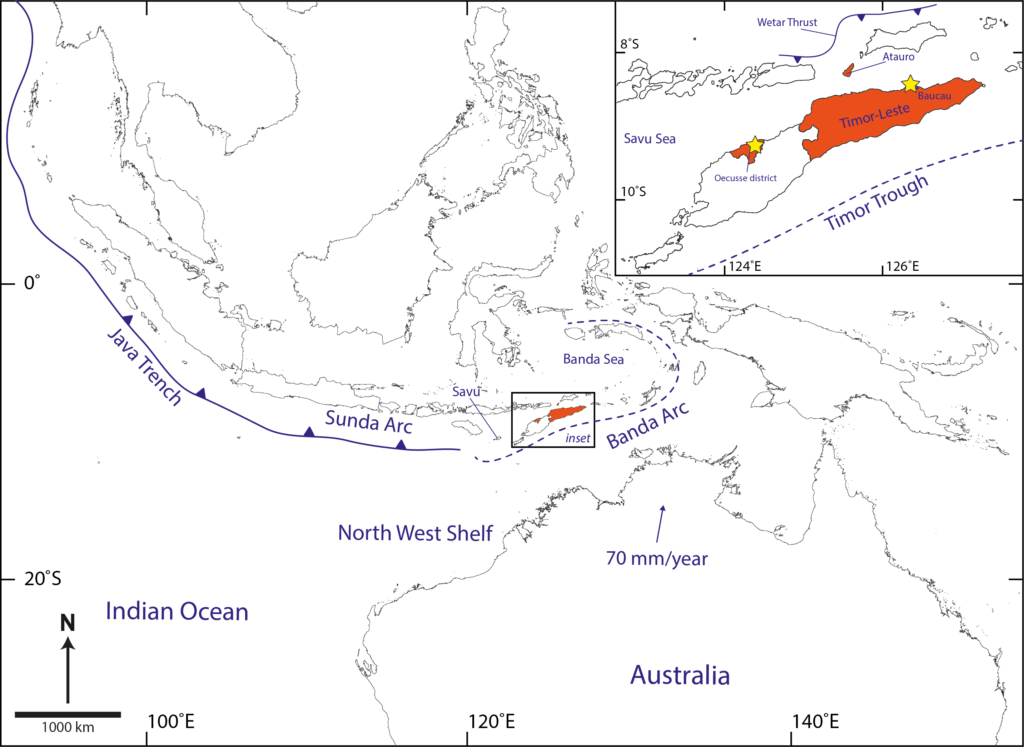

In September – October 2015, I was given a rare chance to do 6 weeks of fieldwork in Timor-Leste in order to map the geology of the Oecusse district, an enclave of Timor-Leste that lies within Indonesian West Timor. This formed part of my Masters research which looked at the pillow basalts of the Oecusse Volcanics, a brilliant mountainous exposure outcropping on the north-east coast of the Oecusse district. My research aimed to characterise the neotectonic evolution of Timor (<~15 Ma), which is a relatively young orogen that formed following the collision between the Australian continental shelf and the Banda Arc subduction complex.

Our journey began in Dili, the capital of Timor-Leste. Accompanying me was my supervisor Dr Steven Boger, fellow Masters student Jack Percival, and Timorese geophysicist/local guide Francesca Joe Magno – together we were known as Team Timor. While we were eager to get to Oecusse quickly and begin our field campaign, I was quick to realise that the local atmosphere was one of relaxation and waiting, with no one rushing around to get things done hastily – a phenomenon I called “Timor Time.” As such, we spent our first week in Timor meeting with government officials from the Institute of Petroleum and Geology (IPG) while attempting to get visas from the Indonesian embassy to drive across West Timor. This was a little frustrating, considering that if we had flown into Indonesia, we would have been given free visas on arrival, but instead, we had to wait in a long line one afternoon to pick up a number just so that we could wait in the actual line on the next day where we could put our forms in – a great example of Timor Time.

Of course, we did not waste our time waiting around Dili. We mostly spent our idle periods checking out the local geology around Dili in order to get our eyes adjusted to some of the major units – these rocks were quite different to the turbidite sequences in Victoria! Joe tells us that foreigners are called malae in Tetun – the national language, although in some instances I was referred to as China-malae owing to my Asian heritage. We decide to do some malae activities, such as checking out the local beaches and eating fried chicken burgers. Joe also warned us about maningas, which are voodoo-like charms women can use to infatuate men!

Jack hammering out some Hili Manu Lherzolite for his own project – there were mountains of this stuff!

When we had a few days to spare while waiting for the visa to come through, we travelled east to the town of Baucau, where pillow basalts had previously been reported. Roads are a bit dodgy in Timor, with very limited bitumen once you get out of the capital so it took a while to get there. Baucau is a much smaller town than Dili and lies on a slope consisting of young limestone terraces with natural spring water flowing through the town. We hiked for hours across razor-sharp limestone along a crystal-blue beach, and ultimately we found the pillow basalts and sampled them via a quick downward climb.

After our successful search in Baucau, we headed back towards Dili where our Indonesian visas were ready to go! We drove towards the Indonesian border along the coast, stopping at the notorious town of Balibo before staying at a guest house in Batugade for the night. In the morning we rendezvoused with the rest of our convoy, which included two Timorese geologists from IPG – Joao Paulo Soares Dos Reis and Albino Da Silva, and then proceeded to cross the border.

We crossed the border at Wini, but not before driving through the spectacle of the Oecusse Volcanics mountains. After hours of visa applications and waiting in lines, it was a relief to finally be in Oecusse where we could start the bulk of our fieldwork.

Team Timor crosses the border into the Oecusse district! The asymmetry and tilt of the photo is because the security guard who took it had never used a camera before.

We spend our first full day in Oecusse driving around the district and exploring small villages with our local geologist team members. They take us to one of the better known geological sites in Oecusse – the active mud volcano fields. I had never seen anything like this before, but found it extremely fun to dance around the many vents bubbling out mud. We were told that the mud was not hot, although the sight of bubbling mud had strong connotations for me to volcanic activity. My worries soon disappeared after I confirmed the cool temperature of the mud with a good ol’ fashioned touch-test. One of our team members (who shall remain unnamed) found out that parts of the surface were made up of only a very thin layer of mud-crust, resulting in the “mudification” of his leg, and the near-loss of his thong (aka flip-flop/jandal to those playing at a non-Australian home). Not soon after, another team member fell in waist-deep but was lucky that two people were nearby to pull him out. Team Timor is proud about its zero-casualty history.

Fun and games aside, we began our proper fieldwork the next day visiting some amazing pillow basalt outcrops from the Oecusse Volcanics. This formation outcrops from the coast up to about 1200m above sea level in the northeastern part of Oecusse. The terrain becomes quite jagged and steep in many places as a series of dykes have been preferentially eroded out. This made for some tricky hiking at times, with most of the mountains covered in thick, thorny bushes.

In the Oecusse district, many of the villagers only spoke Baikeno, which is their local district language. Our standard interactions with the locals started with our district guide Julio Boquifai, who would talk to the villagers and translate from Baikeno to Tetun, then our Timorese geologists would translate from Tetun to English for us, and then it would go back the other way. This made conversation a bit tricky, and we suspected a bit of Chinese whispers happening when the locals began laughing.

Myself, Joao Paulo, Albino, Jack, Steve and Joe conquer a thorny hill to get a nice view of the Oecusse Volcanics in the background

On one occasion towards the end of the field season, I wanted to hike up to one of the high-points of the Oecusse Volcanics as the satellite image showed a pseudo-plateau with a change in colour. It was planned as a full day hike, however not everyone came fully prepared. We embarked with our team of nine which included a boy from the adjacent village as a local guide. After climbing up the first ridge, several of the Timorese team members decided to head back, worried that their casual footwear and meagre water supplies wouldn’t get them through the day. More team members peeled off, until it was just Steve and myself left. And so we journeyed on, eventually reaching the top after hours of trudging along without a cloud in the sky, and to our delight we found nothing but the same old pillow basalt that we had been looking at throughout the entire trip. It was a bit of an anti-climax, but we had a nice view at least. The hike down was even harder as the Timor sun beat down on us and our water supplies were dwindling. We made it to the first ridge we had started from, but forgot how steep it was, especially with loose pillow basalts acting as ball bearings. It was then that we heard some dogs barking rather aggressively. They were accompanied by a local man who was running up the steep hill barefoot. They were chasing a full grown monkey and were able to corner it up one of the few tall standing trees on the hill. With a single throw, the man launched an orange-sized lump of pillow basalt and hit the monkey square in the head, which then came plummeting down to the ground. The man’s children then proceeded to collect the monkey and whacked it against more basalt to finish it off. Steve and I watched in awe, semi-delirious from dehydration, but luckily for us, the man and his kids showed us a path down the hill – just follow the monkey-blood road! When we finally arrived at the bottom, we found the rest of Team Timor sipping on fresh coconuts and drinking coffee with the villagers!

The rest of the field season was spent driving around the district along precarious tracks as well as up and down the dry river beds as far as we could (although on one occasion a local river worker used his digger to build us a road). Most of the land is dominated by subsistence farms with very basic infrastructure. The people in the small villages we passed through were extremely friendly, one farmer even climbed up his coconut trees to treat us with afternoon refreshments. Often children would yell out “Mister, Mister!” to us malae waving back at them. Some would also greet us with various forms of bondia and botardi (good morning and good afternoon) which led us to calling our Land Cruiser “Mr Botardi.”

The guest house we stayed at provided breakfast and dinner for us. Breakfast usually consisted of a pile of freshly baked bread rolls paired with a pile of fried eggs. Accompanying this would be different combinations of soggy, mildly-warm chips (as in French fries), doughnuts, fried bananas and other local delicacies, as well as freshly brewed Timorese coffee. Lunch was generally similar, with the addition of a jar of Vegemite that was bought back in Dili. A few of the locals tried it to their distaste, and it quickly became known as keiju-malae, which translates to “foreigner cheese.” If a small restaurant was nearby, we could stop for a warm can of Coke and some fried fish, miscellaneous pork bits and rice. Also, the Indonesian chocolate-wafer things called “beng-bengs” were a common and welcome field snack. For dinner we would be treated a feast of Timorese delights. The local food is a bit of a mix between Malaysian/Indonesian, Portuguese and Chinese flavours, as well as fan-favourites such as papaya flower buds, fried chicken and of course – soggy, mildly-warm chips!

The field season drew to a close, which was a bit sad but we had plenty of fun and had collected a whole swag of new rocks to analyse. We packed everything up and said our goodbyes to the guesthouse, but not before picking up our very own tais (Timorese woven fabrics) which had floral designs characteristic of the Oecusse district. We organised to take the overnight ferry back to Dili with both of our 4WDs on it. Some of the team sat up in the proper passenger area, but a few of us stayed down below where the cars were, this seemed like a fun idea at the time. The whole bottom area was filled with a combination of cars, trucks, water buffalo, goats trying to mount one another, fighting roosters that crowed all night, and people sleeping in the small gaps like Tetris pieces. The ferry moved at a horrendously slow pace, taking over 12 hours to travel less than 150km – typical Timor Time. As the night progressed, the floor became increasingly covered in animal droppings with an ever increasing smell. Some locals were drinking tua sabo (homebrew palm spirit) that they poured out of jerry cans, of which I had a few shots before trying to get some sleep. I ended up taking refuge on the top of Mr Botardi, where a few locals joined me throughout the night and I chatted to them with the small amount of Tetun I had picked up. The cool metal roof was a welcome relief from the hot and humid conditions on the ferry.

I’d recommend travelling to Timor-Leste, a country that is young both politically and geologically. My fieldwork was the highlight of my Masters and having now completed my thesis, I know that there are plenty more geological problems for people to work on!

We asked if we could take a photo of the traditional Oecusse-style lopo house, but they decided to bring the whole family out

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.