Fabiana Richter is a PhD student at the University of Rochester. You can stay up to date with her research here.

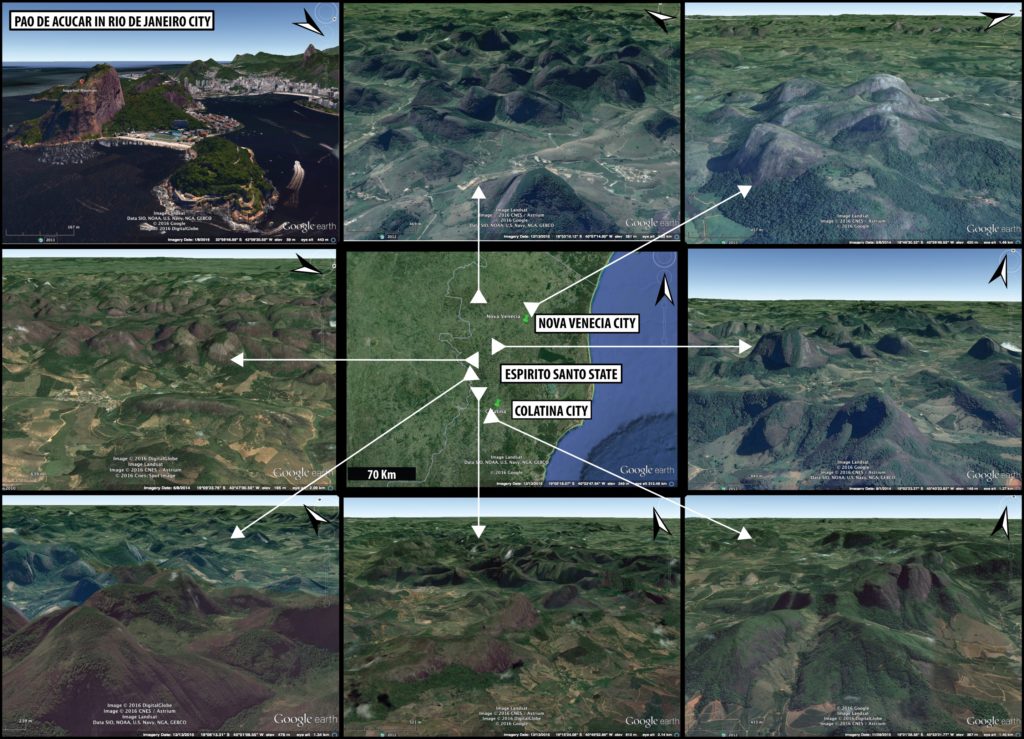

If you have ever seen pictures of the natural wonders of Brazil, you probably have seen a picture of the Sugar Loaf in the Rio de Janeiro City. It turns out that hundreds of Sugar Loafs are exposed inland of Brazil for hundreds of kilometers, forming what some people call a “granitic ocean”. The first figure below, where I indicate some of the locations of these batholiths, will show you what I mean by that.

Figure 1 – The granitic ocean inland of Brazil shown by Google Earth images. The first figure shows the Pão de Açúcar, located in Rio de Janeiro city, for comparison. The central picture is a map that encompasses my study area, in-between the cities of Nova Venécia e Colatina, in the Espírito Santo State, Brazil. All other figures show the location of some of the largest concentrations of granitic batholiths within this area.

These bodies are sections of the mid-crust that formed during the Amalgamation of Western Gondwana, from ~630-500 Ma, as part of the Brasiliano-Pan African Orogenic System. This large orogenic system is subdivided in a number of segments located today in the eastern coast of South America and western coast of Africa. I worked on the Araçuaí Orogen segment, located in Southeastern Brazil, during the end of my undergraduate and during my masters. My field area was located in-between the cities of Nova Venecia and Colatina in the Espírito Santo State, Brazil. This area exposes not only an ocean of granites, but also abundant high-grade metamorphic rocks, which were the main focus of my work. I could spend a lot of time talking about how the peak pressures and temperatures recorded in my samples and the U-Pb geochronology indicate high-amphibolite to granulite conditions attained at peak regional metamorphism from 575 to 560 Ma, but it ends up that you can find everything in this paper. Here I would like to focus on my field area.

First I want to say that I wish I could have done more fieldwork in the area, but then I guess that every single geologist must think the same about their work. Not only the region is amazingly interesting from a scientific perspective, it also has such wonderful sceneries. This is how the roads that cross the Neoproterozoic mid-crust look like:

Granitic batholiths and high-grade metamorphic rocks are everywhere and you have plenty of opportunities to get closer to them.

Figure 3 – Locality near the city of Nova Venecia. On the far side of the picture, Prof. Pedrosa-Soares, Dr. Kathryn Cutts and PhD candidate Marilane Gonzaga observe the features of the granitoid they are stepping on.

But the best part is that there are numerous locations where you can actually observe the cores of these rock masses, and they are also everywhere. For instance, abandoned granite mining sites in the area provide a great view of what was going on inside the Sugar Loafs as they crystallized.

Figure 4 – Abandoned mining site showing the structures and features of the granitoid. From left to right are Prof. Gary Stevens, Prof. Pedrosa-Soares, me, and my main advisor, Prof. Cristiano Lana.

Figure 5 – Another abandoned granite mining site showing roughly a cross section of the top part of a batholith.

Figure 6 –One of the many remaining blocks of granitoids that were left behing after the mining in this location ended. Interestingly, many of these granitoids bear metasedimentary xenoliths. This is me in my first field trip, as an undergraduate student, having no idea what that meant.

Road cuts provide some of the best access to high-grade metamorphic rocks. And the area of exposure is only increasing as more roads are being built in the countryside.

Figure 7 – Paragneisses are widely exposed near the roads and in road-cuts. From left to right are Prof. Cristiano Lana, Prof. Pedrosa-Soares, me, Prof. Fernando Alkmim and Prof. Gary Stevens.

Figure 8 – One of the many exposures of high-grade metamorphic rocks we encountered in the road cuts.

The amount of good exposures is really overwhelming. You can find them even next door to your hotel.

Likewise, the amount of garnets you have to describe observe in the field is comparable to the number of stars in the universe.

And at the end of day you cannot be more thankful for the opportunity to learn more and more about the history of this amazing planet!

Figure 11 – Picture of the ‘Pontões Capixabas’ National Park, in Pancas, Espírito Santo State, Brazil.

Photo by Andrea Bayerl Mongim.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.