Jack Matthews is a postgraduate student at Oxford University studying for a DPhil in Palaeontology and Sedimentology, mainly working on the Ediacaran rocks of Newfoundland and the United Kingdom. You can read more about his research here.

Newfoundland, Canada is one of the best localities in the world to observe the rise of the Late Ediacaran Rangeomorph organisms, and their associated enigmatic friends. These fossils, widely accepted to be the earliest complex macroscopic organisms, still baffle palaeontologists as to their true position within the Tree of Life. While you may have heard of these fossils from the now world-famous outcrops at Mistaken Point, Newfoundland; what is less well known are the equally spectacular assemblages on the Bonavista Peninsula, centered around the Catalina Dome.

Back in 2008, while serving as field assistant to Alex Liu, who was then doing his DPhil research, we went exploring in the Catalina Dome area, in the hope of finding new fossiliferous outcrops. The area had already been searched and described in the seminal paper by Hans Hofmann. However, as well as wanting to observe his localities, we had become aware there were many more out there, and so we worked to document them.

One such new outcrop we discovered was in Back Cove, half way between the small communities of Port Union, and Melrose. To be honest, it didn’t show us anything particularly interesting; a few examples of the abundant discoidal fossil Aspidella and some pretty average Charniodiscus fronds.

Several weeks later the head of our research group, Prof. Martin Brasier joined us in the field, and we took him on a tour of our newly discovered, if mediocre, fossil localities. Returning to the site at Back Cove, while Alex and myself tried to make the discovery of several disks and a frond sound more important than they actually were, Martin hovered around the opposite end of the outcrop, staring at the rock, and then beckoned us over. It soon became apparent we had missed the most important feature on the surface.

The Haootia specimen, viewed on an overcast rainy day (above), and on a dry late afternoon with low angle lighting (below). The right conditions are essential for the discovery and description of Edicaran fossil impressions.

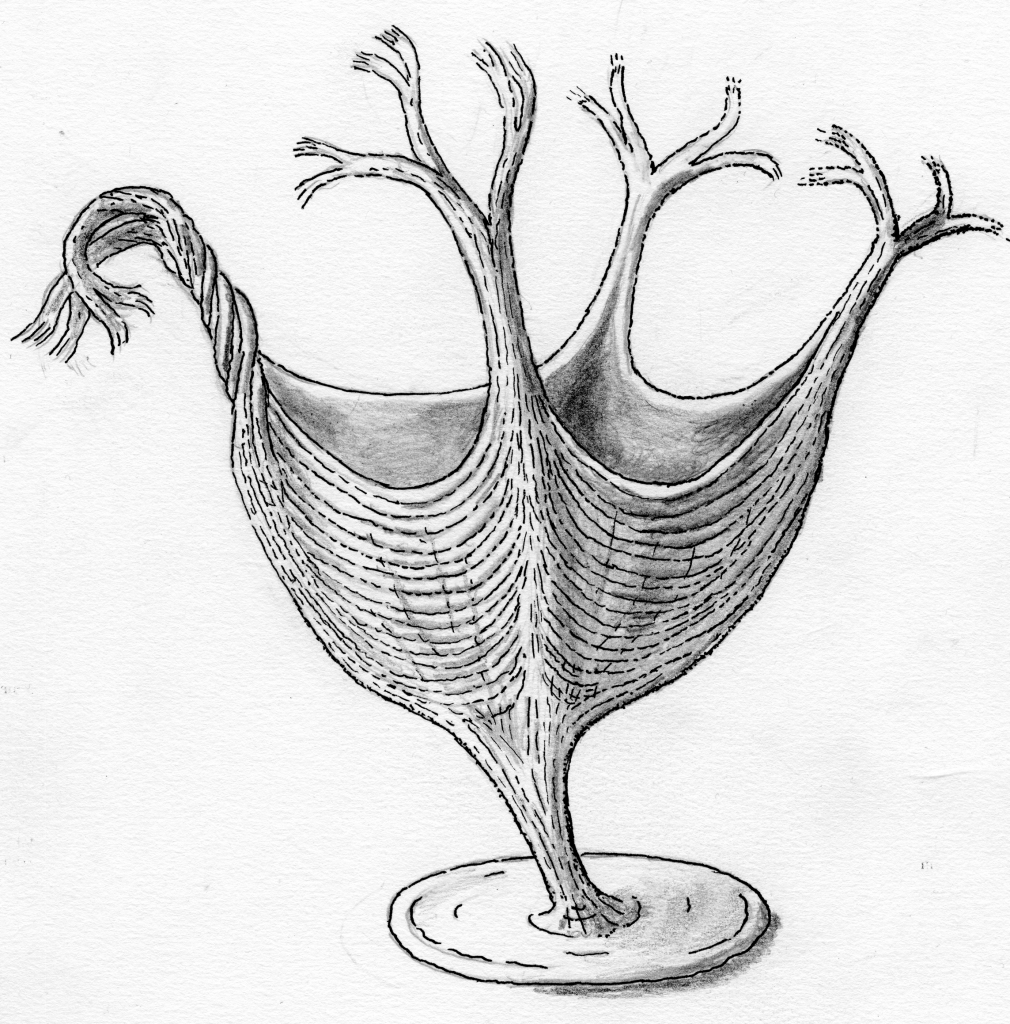

In the low angle light of the late afternoon sun, what was visible was a palm sized area of sub-parallel mm-scale filament structures. Over the next few days, we mused on what it might be, including some slightly less serious options mainly involving alien life. The impression also took on the colloquial name ‘The Wrinkly M’; a reference to the shape the filamentous structures appeared to spell out, mixed with a little joke at our supervisor’s expense (something he is good-natured enough to join in on).

Fast forward 6 years of discussions and debates, and the paper was finally in press. We believe that Haootia likely represents a cnidarian-like organism, with those filamentous structures probably being impressions of the oldest muscle fibres in the geological record. Due to the surrounding frondose fossils, the locality was protected by Provincial Legislation. While we normally like to leave fossils in place in the field so that they can be viewed in the full context of their surroundings, it became apparent that the specimen was at risk, both from theft, and from erosion.

However, before permission could be given, the Provincial Archaeology Office had to be happy with our proposed methodology of removing the specimen. Usually one would take extensive notes and sketches of the locality, and would then have to type everything up into a report and send it over to the Department of Tourism, Culture and Recreation. Instead, I recorded a short video on my smartphone, introducing the locality, the fossils that were present, and narrating my thoughts and preferences for extraction methods. This could then be quickly uploaded and shared – less bureaucracy, more time for fossil hunting! The Department were happy with the results, approved the extraction, and are now looking into using the smartphone-video method of reporting at other localities.

In a contrast to the more technologically advanced methods of communicating my thoughts on conservation, the method of extraction itself was a little more prehistoric. Most Ediacaran fossils to have been actively removed from the bedding planes of Newfoundland have been exhumed with rock saws. As well as being much harder to use in the middle of nowhere, they also scar the surface that is left behind – not so good in a protected area. Therefore we went back to basics, and used a hammer and chisel. Exploiting the cleavage planes, we were able to remove the specimen in 2 large pieces (one estimate to be around 25 kgs, which was a fun haul back to the van, several miles away!) This left the locality with little lasting damage, and a surface that looks just like it would have, had the fossil been washed away by a few winters of storm waves.

Timelapse of Jack Matthews and Alex Liu (lead author of the publication) removing the Haootia specimen.

Haootia now sits, safe and sound, in The Room’s Museum, St. John’s, Newfoundland. It is available for researchers to view, as well as the public, and it seems likely that the ability of scientists to view it in a controlled environment will no doubt reveal new perspectives on this bizarre organism. The process of preserving this fossil has taught me a lot – to not be constrained by the norm if there is a superior and less-time consuming method of doing something, but also, in this age of synchrotrons, laser scanners, and mass spectrometers; to recognise that sometimes, the old ways are still the best.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.